Previous readers of this content may recall my main argument: the libertarian “freedom movement” failed to address racism in the post-World War II United States and often used libertarian arguments to hinder progress for African Americans. However, after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, these freedom advocates surprisingly became focused on issues of racism, particularly “affirmative action” and “quotas.” In an attempt to reconcile their past, libertarians have since attempted to rebrand their “classical liberalism” as always being opposed to racism. These efforts never succeed because the stories they tell are simply unsupportable.

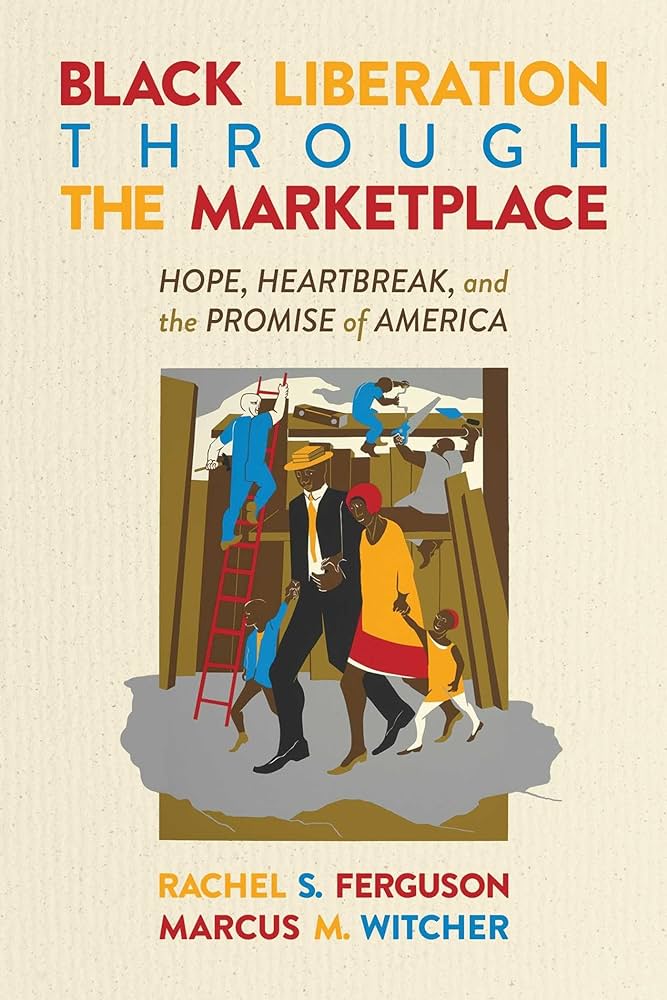

Comes now Black Liberation Through the Marketplace, a book by libertarians, Rachel. S. Ferguson and Marcus M Witcher (FW). It is published by Emancpation Books, which announces itself in this way:

A spectre is stalking American newsrooms and publishing houses: the spectre of angry woke leftists aggressively seeking to dictate the range of acceptable viewpoints on a wide range of issues. This campaign of mob censorship not only runs counter to our cherished national traditions of free thought and speech, it especially limits the expression of independent views by writers of color who may dissent from the majority opinion of their group.

OK then….

FW assert that classical liberalism’s principles of individualism, property rights, free markets, and the rule of law are inherently antiracist, while accounts of the rise of racialized chattel slavery and capitalism are mistaken. But they grapple with little of the enormous literature on these subjects. FW write as if the 1619 project is the last word on these subjects rather than a project meant for public consumption. and Ed Baptist’s decade-old The Half that Never Was is the only book on the topic. The authors assure us that the thesis of “the inextricable association of capitalism with slavery has been roundly criticized by experts as being woefully unfamiliar with the economic literature on slavery” (p. 32). Well, sure. and those experts’ work has been rebutted in turn: historical inquiry is complicated and FW misleadingly write as if this were a settled controversy. More worryingly, they simply act as if some sort of economic calculation has settled the matter rather than even attempting to address the enormous literature on racist ideology and how many classical liberals, John Locke pre-eminently, justified racial conquest and slavery in the language of property rights and freedom.

FW correctly notes that at the beginning of the 20th century, Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois were both striving for Black liberation, albeit through different paths (p. 174). Both leaders sought emancipation from American racial oppression, with Washington believing that economic advancement would lead to white Americans acknowledging Black financial power, thereby granting full legal and political rights to Black citizens. Du Bois, on the other hand, believed that political and legal rights were essential for economic advancement, as without them, Black citizens would be powerless to protect their gains.

While FW argues that the market can lead to Black liberation, they overlook the fact that full political and legal rights are crucial for this to happen, and, more tellingly never tell the reader that the “classical liberals” in the post-World War II US opposed extending those political and legal rights to Black Americans. FW’s own evidence proves that even with economic advancement, the market cannot eradicate racism on its own. Between the end of the Civil War and World War I, FW tell a tale of enormous economic advancement. “Simple competition” meant that “White planters had to choose between their preference for wealth and their preference for discrimination” and found that choosing discrimination had severe economic costs. But wait, then FW tell us that “market forces forced whites to turn to the political realm to maintain supremacy” (p. 79). This means that even though “Black Americans tripled their per capita income by 1914” (p. 80), political and legal equality never emerged through market mechanisms to protect those gains as Washington argued they would. This is the problem with thinking that the market would “solve” racism: there is never any timetable offered, no indication of how long Black citizens would have to remain disenfranchised and suffer discrimination when that happy day arrives when white people will finally recognize them as fellow human beings because, now, they are finally rich enough to be granted full citizenship. This is hardly good enough.

FW highlights the brutal violence experienced by Black individuals during the first half of the 20th century. However, they fail to mention that several devastating massacres against Black people were motivated by the economic progress that was supposed to guarantee their safety in a market economy. In the 1906 Atlanta massacre, the white “mob destroyed Black-owned businesses and homes and targeted the historically Black colleges and universities in the area. A barbershop owned by Alonzo Herndon, one of the nation’s first African American millionaires, was vandalized.” The Tulsa race massacre specifically targeted “Black Wall Street” an important hub of Black economic success. Far from protecting Black people, economic power often made them targets for white violence precisely because Black people lacked the legal and political protections that economic advancement was supposed to bring in its wake. Libertarians frequently assert that the state’s primary function is to safeguard private property. Nevertheless, historical evidence demonstrates that it only defends the property of those who already possess the legal and political clout to demand protection. The market and property, absent the mechanisms of government, cannot survive, contra libertarian claims to the contrary.

In 1955, at the start of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, FW note that “all previous attempts to use Black economic power to end segregation and discrimination had failed” (p. 192). Many things had changed since Washington’s death four decades earlier. The growth of Black wealth in Black social spaces such as churches and lodges had, as FW note, meant that there was a “powerful foundation” for Black protest “built over the preceding seven decades, of Black businesses” (p. 192).

But wait, does that mean that Booker T. Washington and FW are right? That the market did, indeed, make strides toward getting Black legal and political rights. No, not really. It isn’t that the market forced white people to finally concede that Black people were real people. It was that Black people stood up and demanded their full rights as citizens. Nothing was given, it was taken. That Black economic advancement, and tight social networks, made it possible for such demands to be made does not equate with “the market” eliminating Jim Crow.

Du Bois, the NAACP, and the Civil Rights Movement supported of Black economic advancement, but the opposite was not the case. Libertarians, who advocated for market solutions to racism, opposed any political or legal solutions to racism. Libertarians believed that Fair Employment Practices were an unjustified infringement of property rights, and they opposed any requirement for owners of public accommodations to stop racially discriminating. They also argued that the federal government had no business interfering with states administering public education, even if that meant maintaining racial segregation. Libertarians sometimes even supported segregationists who claimed that the 14th Amendment was illegally adopted, thereby relieving state governments of their obligation to provide equal protection of the law. When Virginia proposed a voucher system to maintain racial segregation in private schools, libertarians like James Buchanan and Milton Friedman were eager to provide their support for the project.

The core of the libertarian opposition was what Albert Hirschman called the “perversity thesis” which holds that any attempt to cure a social ill will only exacerbate the very problem it is meant to solve. Of course, if the perversity thesis were true, Jim Crow should have eliminated racial discrimination rather than viciously enforce it, something libertarians never considered. Libertarians consistently argued that implementing a Fair Employment law would intensify racial tension. Libertarians believed that to combat racism, it was necessary to change the minds of racists through persuasion, rather than relying on legal action, holding this belief even as mountains of social scientific evidence against it accumulated. The entire civil rights movement held that legal and political changes could precede attitude change, a view that libertarians simply view as “coercion” rather than freedom and equality. No matter how much retrofitting libertarians attempt to make to their central ideas, the record is clear that their “freedom movement” inhibited this country’s battle against its own racism.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.