Libertarians love making stuff up. I don’t mean the counterfactual stories they tell when you point out some wonderful thing the government has supplied such as the eradication of smallpox, aka World’s Greatest Killer. Facts like that are always met with the response, “Well, a free market would have eradicated smallpox better, stronger, faster.” These fact-free assertions probably make them feel better, but I doubt anyone save the libertarian tribe takes them seriously. As Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway argue, the libertarian free market existed “precisely never. There has never been a time in human history when markets met these conditions, and there is no reason to think that such conditions could ever exist” (p. 418). Nor am I discussing the truly dangerous fiction they peddle to the world, such as the “Great Barrington Declaration” on the Covid pandemic or the fantasy of climate-change denialism, largely fueled by libertarians and their fossil-fuel-burning patrons. Or the “right” to poison themselves with raw milk. Thank goodness we took care of smallpox before the libertarian propaganda machine got going. “The solution is not vaccines but herd immunity!” “Um, actually, there is no proof that smallpox ever killed anyone!” or “It is my right to get a highly contagious disease with a 35% mortality rate! My body is my property!” No, my subject here is the actual make-believe world at the heart of libertarian ideology. If allowed to create a world in line with their politics, what would that world look like?”

Galt’s Gulch

Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged (1957) is for those who think the problems of the world owe to the fact that people aren’t selfish enough and things would be better off if the good people just retreated to Galt’s Gulch and let a few billion people die as a result. These billions are “parasites” and, although Rand does not tell us directly, obviously must include the disabled and children. In Rand’s tale, those looters deserve to die.

Rand’s heroes are Übermenschen who retreat to a mysterious “Galt’s Gulch” hidden in the Colorado mountains and create a capitalist utopia. How does it remain hidden in a state where the federal government owns about a third of the real estate? Rand never explains this problem. In this place, these fierce individualists, beholden to no one but themselves, must take an “Galt’s Oath” named after cult leader founder John Galt to never give anything to anyone. What happens if someone, asserting their individuality does not take the oath? Rand never tells us. True individualism, it turns out is not thinking for yourself but acting and thinking exactly like Rand Galt does. You may want to feed your children and expect nothing in return, but that is a violation of the Galt’s Prime Directive so you should charge them or let them starve. If you choose to give them food, you aren’t an individualist. In Rand’s account, Galt’s Gulch is almost entirely populated by men. We can assume that the rugged individualist man returning home after working ruggedly individualistically is presented a bill by his ruggedly individualistic wife for doing laundry and vacuuming. I assume that she only prepared dinner for herself, and if he wants to eat, that will cost him.

What happens if a parasitic looter enters the gulch? Well, that’s impossible, you see because Galt created a mysterious shield that made the Gulch invisible. Does he give this protection to all inhabitants in violation of his oath? Rand never notes how he is paid for it, nor does she explain what would happen to a free-rider who doesn’t pay Galt yet obviously remains protected from the looters. There is no police force to enforce the (unwritten?) contract between Galt and the inhabitants.

In this capitalistic paradise, there are mineral mines and industrial production. What happens to the pollution caused by these enterprises? Rand is silent on this. Are children allowed (or required) to pay their way by working in a mine with no safety standards? Rand doesn’t say. Colorado has a semi-arid climate and the politics of water use are intense. Rand does not mention of where the water for all this comes from. Even a parasitic looter who works for the State of Colorado would notice the missing water. However, Rand just fiats away any real-world problems and hopes that no one notices them.

Despite her claims that her system is realistic and rational, Rand’s utopia is rife with contradictions and waves away any true problems of the world, “Rand’s utopia is not only inconsistent in description but simply not plausible in reality. Her idealized version of society is flawed in terms of sociological and economic and political laws and rests on a distorted view of human psychology” (p. 258)

Gumption Island

Largely forgotten today, Felix Morley (1894-1982) was a giant of the post-World War II libertarian movement. He won a Pulitzer for his editorial writing at the Washington Post, criticizing Roosevelt and the New Deal. After World War II, Morley wrote regular columns for Nation’s Business and Barron’s Weekly, co-founded the conservative newspaper Human Events, and enjoyed regular broadcast gigs on radio and television:

Morley was also on the advisory board of Spiritual Mobilization, a libertarian organization that promoted free-market ideas to the clergy, and he was a founding member of the Mont Pererin Society. The libertarian Volker Fund awarded Morley the William Volker Distinguished Service Award in 1961.

In 1956, Morley published Gumption Island, a novel he described as a “political fantasy,” in which Gibson Island, where Morley made his home was transformed into a libertarian utopial. Morley wanted to use his novel to both explain his ideal political order and to to explore race relations, “Knowing this island and its people, both white and black, I have long speculated how they would react, individually and collectively, if thrown into a ‘state of nature” (Morley to J.H. Gipson, March 19, 1954, Box 33 in Morley Papers, Hoover Presidential Library). Much more than his non-fiction, Gumption Island reveals the racism underneath Morley’s political thought.

In the novel, the Soviets drop a “Q-bomb” which sends a small island of homeowners back to the age of the dinosaurs and they must create a livable political order. There are two notable aspects of Morley’s politics, as revealed in the book that bear mentioning.

First, Jews controlled money and banking on the island. Albert Adler, one of the island’s few Jews, argued that money had to be fixed to the gold standard to prevent the manipulation of currency by government. He argued,’ For good historical reasons, every intelligent Jew understands the significance of gold. As a matter of fact, between ourselves, I’m wearing a beltful of double eagles at this minute. I’ve never travelled anywhere without them, since 1932. It’s funny to think that now I’ve carried these five hundred gold dollars back fifty million years” (92). Finally, Adler lends the community his gold with the guarantee that there will be no manipulation of the gold reserve and that he and another person will be in complete control of the bank and have the sole power to appoint their own successors. Later in the novel, a motion is made to force the bank to pay the profits of the bank to the island’s Director of Finance. Adler blocks the move by telling the islanders, “If that motion is carried…I may feel it necessary to withdraw the gold reserve, which is not an asset of the bank, but a personal loan of my private property.” Morley thus recreates the stereotype of the money-grubbing Jew, the sole control of the economy.

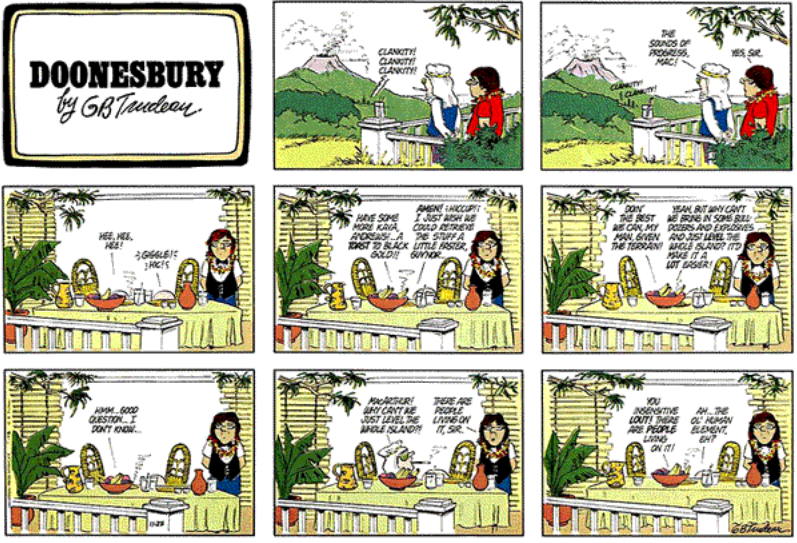

Second, Morley wrote all African-American characters in a minstrel show dialect, even though by the 1950s such a dialect was increasingly recognized as reflecting an ugly racist stereotype. White immigrant characters, such as the Polish immigrant who connived with the Soviets to set the Q-bomb, as well as a Russian pilot who had been thrown into the past with the Gumption Island residents, were presented as speaking unaccented English. While listening to the white islanders discussing Plato, Bill Jefferson, portrayed as a leader in the African-American community, thinks to himself, “I guess…that Ah jes’ ain’t intellectualy competent. With all this yak-yak, they’s clean forgot Ah’s supposed to pick up a load o’ wood fo’ the hospital.” After he returned to the African-American community and reported what he had seen and heard in the white home, they agreed not to participate in governing the island. As one character put it, “I guess we got to leave it to the white folks to give the orders…so long as they treat us decent.” In Morley’s libertarian social order, African Americans happily give up any political power because they realize their own incapacity to govern.

In the 1950s libertarians imagined their utopias as places where pollution didn’t exist, where children were “free” to work or starve, and where “individualism” meant surrendering your free choice to act altruistically. A place where the Jewish racial trait of hoarding gold allowed them to control the economy, and African Americans were happy in their servitude. You and I might call such places nightmares, but libertarians call them paradise.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.