It turns out I have more thoughts on Andrew Koppelman’s new book, Burning Down the House. In my previous post, I dealt with Hayek and racism. Here I focus on Koppeman’s claim that a sharp distinction can be drawn between the crude and radical libertarianism of Murray Rothbard and the sophisticated and moderate libertarian libertarianism of F.A. Hayek. It was Rothbard’s fanatical opposition to any version of the welfare state or regulatory control of businesses that libertarians are embracing today, Koppelman claims. By abandoning such absolutist claims and embracing Hayekian balanced approach to governance, libertarianism can be a useful guide for our future. Koppelman is correct that a clear distinction can be drawn between Rothbard and Hayek but errs in thinking Hayekian thought is not responsible for the libertarian embrace of current policies that Koppelman deplores. I show that Koppelman misunderstands the argumentative strategies employed by today’s libertarians to oppose reasonable regulations on business and the expansion of the welfare state. These strategies are better described as Hayek’s than Rothbard’s. Also, I show that Koppelman’s main intellectual opponent is Hayek himself, who consistently opposed policies that Koppelman claims Hayek’s logic should endorse.

To begin, I will explore Hayek’s argumentative strategy for evaluating a given governmental action.

For Hayek, Koppelman argues, state action could be justified through cost/benefit analysis: does the proposed action’s benefits outweigh the cost? If so, the action is justified, if not the action is not justified. But that description, which reduces Hayek to the kind of everyday cost/benefit analysis that every policymaker presumably employs in some form and misses what makes a particular calculation “Hayekian.”

What makes a cost-benefit analysis Hayekian is that Hayek demanded that state intervention in the economy shouldered very strong probative obligations “Hayek’s view did not entail minimum government. It rather imposed strict conditions on intervention in the economy” p. 15). For Hayek, the market enjoyed a strong presumption of efficiency and, in order to justify State action, the government should shoulder a quite heavy burden of proof to show that the benefits of taking action outweigh the costs imposed. The state may act in “market failure can be shown.” (p. 177). Koppelman argues that Hayek, read properly, allowed for reasonable regulation of economic activity in order to protect the public good and a welfare state provided those measures met very stringent evidentiary requirements showing them to provide net benefits to society. For Hayek, that could include things like a guaranteed minimum income to provide for basic human needs. These reasonable measures are viewed as anti-libertarian by today’s libertarian right, who are committed to Rothbard’s dogmatic views of private property which forbids such measures. For Rothbardian thinkers, taxation is always theft, state action is always coercive, and the market will always provide for human needs better than the government–views Hayek rejected according to Koppelman. Koppelman concludes, “Hayek’s reasoning thus yields a moderate, pro-capitalism, pro-free trade philosophy that embraces the modern regulatory and welfare state so long as it does its job properly’ (p. 71).

Well, now. Before we all go jumping into bed together, let’s ask ourselves a basic question: do Hayek’s views provide the guidance necessary to actually govern in the way that Koppelman claims it did in the past and should in the future? If the question of state action turns on how much evidence is required to overcome the presumption the market enjoys, for Hayekians, that means the evidence needs to be very good and there needs to be a lot of it. But who makes the determination that the evidence is sufficient? How is the evidence gathered and weighted? What counts as a “cost” or a “benefit?” Those are the kind of questions that need answers before a political theory can guide policy.

More importantly, since there is a strong presumption against state action in Hayek’s formulation, those opposing regulations or a welfare state do not need to “win” any particular argument about such actions. They merely need to set the burden of proof high enough such that it is difficult, or perhaps impossible to meet, as Richard Gaskins has shown. Schematically, the argument looks like this:

- Make the opposing advocate shoulder the burden of proof.

- Set the standards for meeting the burden of proof very high.

- Claim that the opposing advocate has not met the burden of proof either by claiming the available evidence does not meet the burden of proof OR that the available evidence does shows the costs outweigh the benefits.

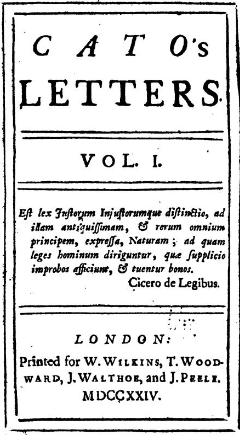

In fact, this is precisely the strategy employed by the“neo-Hayekians” who are homed at “intellectually serious policy-wonk institutions such as George Mason University and the Cato Institute” (p. 110) to forestall the kind of “modern regulatory and welfare state” Koppelman claims they should be embracing.