The Strange Parallels Between a Noted Libertarian’s Writings and Those of the Antisemitic Right

In those pre-PC days it was apparently OK to use a cruel nickname

While not a household name as much as Ayn Rand and Milton Friedman are, Floyd Arthur Harper (1905-1973), who wrote under the name F.A. Harper and who was known to his friends by the ungenerous nickname “Baldy,” was an important figure in the post-World War II libertarian movement. Baldy Harper is remembered more for his organizational prowess than his writings, but comparing his writings to that of the racist right of the 1950s shows how much the libertarian rhetoric of “freedom” served the ends of the racist right.

An agricultural economist, Harper moved from Cornell University in 1946 to join the staff of the Foundation for Economic Education (FEE), Harper, who moved further and further right in the 1950s into the camp of “anarcho-capitalism” with Murray Rothbard, left FEE in 1958 to join the staff of the William Volker Fund, which had been subsidizing libertarian thinkers and publications throughout the 1950s. At Volker, Harper pitched his idea of the “Institute for Humane Studies” (IHS) an educational outreach institute to push free market principles and ideas. Unfortunately for him, his ideas were insufficiently Christian for the Fund’s manager, Harold W. Luhnow, who had fallen under the spell of R.J. Rushdoony, who believed that libertarianism had to be grounded in his own particularly narrow form of Calvinism. Rushdoony’s influence eventually led to the collapse of the Volker Fund but Rushdoony’s malevolent influence on the country is still alive today.

Harper, cut off from Volker funds by the early 1960s, founded the IHS in his garage, but it it still around and associated with George Mason University thanks to one of Harper’s biggest fans, Charles Koch, he of Democracy in Chains fame, who subsidizes the enterprise generously.

Perhaps Harper’s best known book is Liberty: A Path to Its Recovery (1949). In some ways, it serves as evidence of Rushdoony’s orthodoxy that he considered Harper insufficiently reverent: “There exists a Supernatural, ” Harper wrote, “which guides the affairs of the universe.” The moral laws, for Harper, were as real as the physical laws. All this was fairly standard libertarian doctrine of the time. The unique thing that Harper brought to the table was a pseudo-Darwinian account of human progress. Harper believed that progress was generated by the “variation,” i.e. the bell curve distribution, which “seems to pervade the universe” (p. 135). Everything exists on this “normal” distribution, and social progress is achieved when the exceptional men at the end of the curve are free do do as they please.

Despite his quasi-biological argument about human variation, I’ve found no evidence in Harper’s writing that he was interested in race at all. Indeed in Liberty: A Path to Its Recovery, Harper comes close to denying that “race” has any meaning at all:

When one views the members of another race, with which he is unfamiliar, they all seem to be alike until on further acquaintance their differences come to be more and more evident to him; eventually he finds them to be as great as the differences among members of his own race. (p. 135)

Harper’s unusual focus on the biological distribution of traits does not mean there are no familiar themes in his work worked into his biological analogies. Harper contrasted men’s ability to choose, what Harper called the “Blessings of Discrimination,” that of the social insects, who were slaves to their programming. Thus, the free market, in which Men were always free to make a choice, was in harmony with the natural law of human liberty, quite unlike the coercion of the state. Contrast, for example, the condition of an individual’s relationship with his employer with the individual’s relationship with the State. An employee always has a choice:

The slave, if he should object to his plight for any reason whatsoever, cannot move to a new situation of greater promise, nor can he leave to start a business for himself, nor can he quit work to live in retirement on his savings; he must continue to work where he is, in spite of his wishes, and continue to be subject to the dictates of the master. The employee, on the other hand, is free to make these changes; he may bargain with his employer, or he may leave for employment elsewhere, or he may start in business for himself; or he may choose to retire and not work at all, or work only part time, living on the savings he has accumulated. (p. 101)

But the State is always coercive and taxation is the equivalent of slavery:

If the master be the State (government, at all its levels), does the test of expropriated income still serve as a useful measure of liberty? Does the test that has been applied to a privately-owned slave still apply here?

…

This rule is still valid even when it is government that does the taking. If the government should take all that is produced, as does a master from his slave, all the citizens would then be the economic slaves of that government. (pp. 102-3)

Harper also wrote one of the only responses to Brown v. Board of Education I have been able to find in the libertarian literature. Brown found that segregated education was unconstitutional. Harper criticized the decision, not for the outcome about which he remained silent, but for the reasons for the decision. Brown held that regardless of the quality of the segregated facilities, “To separate them from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone.” I have written a whole damn book about this argument in Brown which you should definitely buy.

Harper’s piece appeared in 1955, a year after the decision. He argued that Brown was a “Decree of Racial Inferiority” because:

Is NOT this opinion clearly discriminatory against the Negro race? It is, beyond question, based on the idea that the exclusive company of Negroes in school is somehow lacking in educational opportunity. If the nine Supreme Court Justices did not themselves each believe that Whites are superior to Negroes, surely they would not have supported the opinion which says, in effect, that Whites are superior to Negroes.

I have argued elsewhere that this argument misunderstands the Brown opinion. What interests me about Harper’s piece is why did it appear in 1955, a year after the decision? Perhaps he just read the opinion late, perhaps the Freeman where it was published had a backlog of pieces and it waited in the queue for a year. Or, perhaps it was because Harper read this:

In the two nation-shattering decisions made by the Supreme Court the question of Negro racial inferiority was considered. In the Dred Scott case Chief Justice Taney considered the concept held by certain white men that the Negro was so inferior that it was a blessing for him to be enslaved by the white man. In the School Desegregation decision Chief Justice Warren imputed to the Negro a sense of inferiority when placed in Negro schools with Negro teachers.

This second quotation was also published in 1955 by Earnest Sevier Cox, the white nationalist committed to repatriating all African Americans “back” to Africa. Cox, if you remember, was the ideologue behind the 1924 Virginia Racial Integrity Act and continued to push for the repatriation of African Americans until his death in the 1960s. It is possible, but this is purely speculation, that Harper was inspired by Cox to make the same argument for the Freeman. We do know that Harper read such literatures a little later in his life.

At the very end of Cox’s life, Willis Carto published Cox’s articles and ideas in Western Destiny. “Western” can be a bit of a code word for the racist right to signal: “We are defending white people” and you can still find their outlets using it.

The stylesheet for Western Destiny advised authors to “use Yockeyite terminogy whenever possible.” It was filled with stories about the “culture distorters” (Yockey’s name for Jews) endangering western civilization, reports from Sir Arthur Keith and his supporters explaining how racial separation is necessary for the biological survival of the human race, and articles about the urgent need to ship all those “Negroes” to Africa.

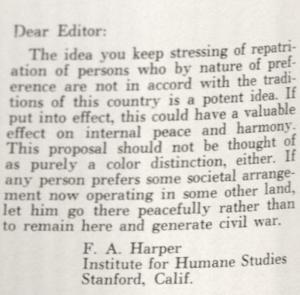

We know that Harper read Western Destiny because they published a letter from him:

Harper, F.A. 1965. “Letter to the Editor.” Western Destiny 10 (5): 2.

Harper reading Western Destiny is no evidence that he was a closet antisemite or racist. Heck I read the online equivalents all the time. Of course I don’t write to them saying, “Here’s a good idea!” as Harper did. Harper’s letter is a nice little case study of how polysemy could operate to make libertarian arguments welcome in racist discourse.

“Polysemy” is simply a fancy word for “multiple meanings.” Polysemy can operate in different ways, and I would like to use rhetorician Leah Ceccarelli’s concept of “resistive reading” in which audiences read texts against authorial intention. In other words, I am not arguing that Harper was a closet racist who wanted to throw his lot in with Carto’s. I am arguing that his argument was ambiguous enough to be have a racist meaning that is actually supported by the text itself. He might have meant one thing, but the editor of Western Destiny, the notorious Roger Pearson, must have read it to mean something else or he wouldn’t have printed it.

Harper called the idea of repatriation a “potent idea” that “if put in effect” could have a “valuable effect on the internal peace and harmony” of the country. Far better for malcontents to leave than to stay here and “generate civil war.” Western Destiny readers knew full well that two races could never live together in peace and harmony and that a race war was imminent; especially in 1965.

Probably attempting to inoculate his endorsement, Harper tried to make clear that his ideas about repatriation were not about “purely a color distinction” but “any person” who “prefers another social arrangement.” Unfortunately, readers of the Western Destiny knew well that the Jews, the “culture distorters” were white, but also that they were an alien presence in the United States. Hence, they gotta go. This belief is still very popular with today’s alt right.

I don’t know if Harper meant any of this when he wrote his letter. However, it is more than likely that is how Western Destiny‘s audience received it. They read it against authorial intention and their reading could be supported by the text itself. This situation is similar to James Buchanan blithely announcing he was against coercive segregation and “involuntary integration” unaware that he was parroting a standard segregationist trope. He might have meant just some standard libertarian boilerplate but in its social context served to support the segregationist cause.

Harper’s opposition to coercion is obvious in the final sentence: “if a person prefers some other social arrangement…let him go there peacefully.” And, this too, would resonate with Western Destiny‘s readers. For this is our country. Carto’s readers believed this was a white man’s country: those black folks and Jews should get out of our country. Harper said the same thing: you don’t like it here? Leave. We urge you to leave. You are not welcome.

That they should be the ones to leave if they don’t like it here never occurs to the folks making this argument. Country not white enough for you? Find one that is, we’ll try to limp along without you, Richard Spencer. It never seemed to occur to Harper, or to any other libertarian I have read, that we have a free market of nations to choose from. You don’t want to pay taxes? Cool. This isn’t East Germany, you can leave whenever you want to leave. Let the market of the world supply you with your preferred living arrangements. Go Galt! Please! How can we miss you if you won’t go away?

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Pingback: Libertarians in the Civil Rights Era | Fardels Bear

Pingback: Ayn Rand on Racism | Fardels Bear

Pingback: Charles Tansill: A Case of Libertarian Nazi Blindness | Fardels Bear

Pingback: Objectified Inegalitarian Objectivism | Head Space

Pingback: The Return of Libertarians in the Civil Rights Era | Fardels Bear

Pingback: Answering the Twittertarians | Fardels Bear

Pingback: Arthur Jensen and His Nazi Friends | Fardels Bear