Note: if you are here because of my discussions of Nancy Maclean’s book, I have several follow-up posts to this one:

- Davidson and Buchanan: Why Phillip Magness Should Apologize to Nancy MacLean

- Reflections on Libertarianism and Racism

- School Vouchers, James Buchanan, and Segregation

- Arguing With Libertarians

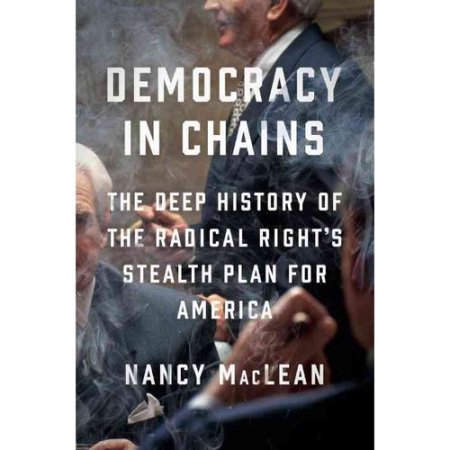

This is the cover a new book by Duke historian Nancy MacLean. I was dreading reading it because MacLean is a terrific historian; I’ve long admired her history of the twentieth-century Ku Klux Klan, Behind the Mask of Chivalry. This new book appeared to be the history I am working on: its thesis is that the white south’s program of Massive Resistance to Brown v. Board of Education was the start of the right wing’s current attempts to disenfranchise voters and to undermine democracy in order to let the free market operate.

MacLean’s book turns out to be much different from the one I hope to write; her focus is on economist James M. Buchanan who moved easily in the corridors of power in Virginia and beyond. The folks I’m interested in consider Buchanan a pseudo-libertarian for these very reasons. In many ways, MacLean’s book is a story of the straightforward successes of libertarians and I hope my work can complement her achievement.

Needless to say, the libertarians, particularly those of Buchanan’s “Public Choice” school, are not happy. Not at all. They feel MacLean has misrepresented Buchanan and public choice theory and, worse, committed historical malfeasance by altering quotations and quoting out of context. There is a lot of dust in the air right now, and a lot of charges being thrown around. Rather than trying to sort out everything going on, I’ll focus on one particular question:

Was James M. Buchanan a Racist?

The Big Picture

If you read the comments on this article, you find comments that MacLean’s book is a “slimy political campaign” and “she painted [Buchanan] as racist. How is that not trashing?” Others ask: “Could you please cite any evidence for the claim that Buchanan was openly opposed to Brown?”, and claim “There is no evidence Buchanan opposed Brown. None at all. MacLean made that up.” One reviewer argues:

“Buchanan wrote very little on Brown or the ensuing school desegregation, and the archival evidence she presents from his papers is both thin and far short of the smoking gun she implies it to be. Instead, she sets out to strengthen her portrayal of Buchanan as a segregationist by tying him to other known segregationists. “

Let’s think about this for a moment: in Virginia in the 1950s, the Brown case and school segregation was the issue of state politics. These writers think the fact that Buchanan wrote nothing about it absolves him of wrongdoing. But, they misunderstand MacLean’s argument: it isn’t that Buchanan and other libertarians actively disliked African Americans. It was that they didn’t care about them. They saw Massive Resistance as an opportunity to advance their own political agenda, which just happened to match that of the segregationists. As for black citizens of Virginia, libertarians did not care about them even enough to address their needs or concerns. It was not hostility, it was indifference that MacLean documents.

Was James M. Buchanan a racist? It is an immensely difficult question to answer and, here’s the thing: MacLean doesn’t attempt to answer it; indeed it is not a question she even asks. In some sense, the answer is a trivial one: Buchanan was born in 1919 in Tennessee, where he spent his formative years, and as an adult he lived in Virginia, ground-zero for “respectable racism” in the decade after Brown where his political allies and many of his colleagues were segregationists. Given those facts, it would be a remarkable thing if Buchanan did not think, at some level, that black people were not as good as white people in his heart of hearts.

MacLean, however, is not interested in what is in Buchanan’s heart regarding race. What she cares about is his actions and his public statements. In those, she clearly shows, Buchanan worked hard to support every move the segregationists made in Virginia. Who cares if he did so because he was defending some strange view of “liberty” rather than white supremacy? The effect at the time and the place were the same. So, was Buchanan a racist? Who cares? What is important is that he worked hard in support of racist policies in Virginia in the 1950s, which is what MacLean shows.

So, if we take the book as a whole, we find that MacLean shows that Buchanan was embedded in a state power structure where only those folks who were reliably segregationist were allowed to work (the famed “Byrd Machine” of Virginia), that he did nothing to rock that boat, and that his theories and arguments were welcomed by those looking to preserve segregation. Was he a racist in his thoughts and beliefs? Not an important question at this point.

The Problem of Inaccurate Quotations

The Devil’s in the Details

So, prima facie, it does not seem outrageous that Buchanan worked hand-in-glove with segregationists in complete indifference to the rights and fortunes of African-American citizens. But, what about the charges that she makes claims without supporting evidence, or quotes out of context? This kind of fine-level analysis may indeed be damaging to her case. So, it is worth examining a few of those claims regarding Buchanan and racism.

Let’s start with a easy one. Easy because it is not Buchanan but our old pal, Frank Chodorov. Chodorov is only mentioned once in MacLean’s book when she lays out her case that libertarians were happy to work with the segregationists. She offers Chodorov as a bit of supporting evidence. One commenter argues: “[MacLean] claims that libertarian Frank Chodorov praised southern resistance to Brown. This is false, he in fact praised Brown in the very article she cites.”

But MacLean did not claim that Chodorov “praised southern resistance to Brown.” She notes, quite correctly, that Chodorov saw southern resistance as an opportunity to reduce or even eliminate public schooling, which is quite correct. The claim that Chodorov “praised Brown” is equally suspect. If he did it was quite faintly in my opinion. The article in question is here, so you can judge for yourselves.

She quotes him accurately in in the proper context. The proper context is this: “Eschewing overt racial appeals, but not at all concerned with the impact of black citizens, they framed the South’s fight as resistance to federal coercion in a noble quest to preserve states’ rights and economic liberty.” (MacLean, p. 50) This perfectly summarizes both the segregationist and libertarian lines in the 1950s. Chodorov’s writing at the time backed up the segregationist position right down the line: He praised Virginia’s move to privatize education, declaring himself agnostic on which side of the segregation issue is right or wrong. He opposed civil rights bills. And we already know he opposed fair employment measures. It is not that libertarians were racists, it was they they did not care about black people. One simply cannot find in libertarian literature of the time ANY concern about the special problems faced by black citizens. And, libertarians somehow convinced themselves that the problem of race would disappear if only we embrace every policy position recommended by the racists.

If we turn to Buchanan who is, after all, the subject of the book, things do not look a whole lot better for the critics. Many point to MacLean’s linking of Buchanan’s thought to that of James C. Calhoun, most famous for his vigorous defense of slavery in the 1830s. MacLean argues that Buchanan’s thought about majority rule and Calhoun’s were remarkably similar. Critics have seized on this argument, perhaps because MacLean makes it on the first page of the book, thus sparing the critic from reading further before declaring her a bad historian. This link between the Calhoun’s and Buchanan’s thought is criticized, rather sloppily, over at the National Review. It is actually better stated on the comment thread I’ve quoted from before:

For example, she devotes the entire preface to John Calhoun, whom she claims was a major influence on Buchanan and libertarianism more generally. This is false (Buchanan, for example, never cited Calhoun, despite citing many other scholars; the entirety of her support for Calhoun’s influence on libertarianism is one citation to an article by libertarian Murray Rothbard, who himself was clearly most influenced by Ludwig von Mises and Ayn Rand, not Calhoun)…. MacLean appears to have fabricated a claim out of thin air.

This is not the only place reviewers have attempted to refute MacLean’s case by determining whether or not Buchanan cited this or that author. Elsewhere in the thread another critic argues, “MacLean asserts that James M. Buchanan was deeply influenced by the segregationist Agrarian poet Donald Davidson… Davidson is never once mentioned in Buchanan’s entire 20 volume collected works.” I found this strategy rather odd until it was pointed out to me that those 20 volumes can be easily searched online. Thus these critics can read the first page of the book, do a search for “Calhoun” online and show that MacLean is a dishonest researcher in the space of five minutes! Easy peasy!

This strategy is also known as the argument from ignorance: assuming that absence of evidence is evidence of absence. Unfortunately, not only do the critics look in the wrong place for evidence, but they misunderstand the very claim MacLean is making. She is expressly not arguing that Buchanan was directly influenced by Calhoun or that he was a “major influence” on Buchanan. What she does claim is that Buchanan’s thought “mirrors” (p. 1) that of Calhoun regarding democracy. That there were parallels between the two schools of thought. She then points out these parallels do not stop with Buchanan, but reoccur in many libertarians funded by Koch, such as Rothbard.

But, where did MacLean get this crazy idea that there were similarities between Buchanan’s thought and Calhoun’s thought? Where did this “smear” originate? Turns out, if you actually read the footnotes she supplies (p. 245), MacLean cites public choice scholars themselves who explain their debts to Calhoun. These articles have titles like “The Public Choice Theory of John C. Calhoun” and “Calhoun’s Constitutional Economics.” This is hardly “fabricating a claim out of thin air.”

The abstract of “Public Choice Theory of John C. Calhoun” reads:

We treat John C. Calhoun as a precursor of modern public choice theory.

Calhoun anticipates the doctrine of public choice contractarianism as devel-

oped by Buchanan and Tullock and expands this approach in original direc-

tions. We consider Calhoun’s theory of why democracy fails to preserve liberty

and Calhoun’s suggested constitutional reform, rule by unanimity. We also

draw out parallels between Calhoun and Hayek with regard to theories of social

change and Hayek’s analysis of “why the worst get to the top.” The paper

concludes with some remarks on problems in Calhoun’s theory.

This is the exact argument MacLean is making. To be sure, the public-choice authors note some differences as well as similarities between Calhoun and Buchanan’s thought, but it seems Calhoun’s influence on public choice theory originates with the public choice theorists themselves. In the article, authors also note that Calhoun’s vigorous and lifelong defense of slavery was an “ethical error” but apparently not a political one. They feel that this ethical error can be easily weeded out from Calhoun’s political philosophy but are notably silent as to how that would be done (p. 672).

Calhoun came back into fashion in the 1950s: published by conservative presses, lauded by segregationist James J. Kilpatrick (still lovingly preserved at neo-Confederate websites) and libertarians alike. Libertarian Felix Morley reviewed the first volume of the collected papers of Calhoun in 1960 praising Calhoun as “easily the most gifted of our

post-revolutionary political philosophers” (p. 312) but never once mentioning slavery as a topic of interest to Calhoun.

Today’s libertarians face a similar problem that Morley faced half a decade ago. Morley obviously adored Calhoun’s anti-democratic political philosophy, but obviously could not defend slavery; thus slavery simply disappears as a topic in his treatment of Calhoun’s thought. Today’s libertarians admire Calhoun and Buchanan, but they cannot possibly admit that those figures were involved in racial segregation; thus segregation disappears as a topic. We saw the same thing with Constitutional originalists: That the theory was used for decades to defend racial segregation is simply ignored. MacLean has shown how Buchanan did work in an alliance with segregationists. Public choice theorists must face up to this fact as a flaw in their system of thought or admit that they have no answer to her case. They have not yet done so.

Note: if you are here because of my discussions of Nancy Maclean’s book, I have several follow-up posts to this one:

- Davidson and Buchanan: Why Phillip Magness Should Apologize to Nancy MacLean

- Reflections on Libertarianism and Racism

- School Vouchers, James Buchanan, and Segregation

- Arguing With Libertarians

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

I agree that libertarians (I’m not one) have a history of allying with segregationists, but the Chodorov article does not say what MacLean says it does. She writes that Chodorov was among the “pioneering northern libertarians … who all but lined up to show their support for the Virginia elite”.You write: “If [Chodorov] did [praise Brown] it was quite faintly in my opinion.”

Actually, Chodorov devotes his first three paragraphs to a long paean to the development of liberty, clearly showing where his sympathies lie, calling the moral pressure on the court to rule as it did “overwhelming”. Later he writes: “The ultimate validation of the Court decision, which ultimately lies amongst the most important in American history, lies in the fact that it is in line with what is deepest and strongest and most generous in our historical tradition”. He does urge “making haste slowly” and preferring “persuasion to force” so that reforms stick, unlike Reconstruction, but that’s not the same as endorsing the Southern states’ “massive resistance”.

I agree that Chodorov was *at best* willfully naive about what private schooling would mean in practice, at worst willing to sell out the black population for his hobby horse of school privatization, but that’s a weaker claim than what MacLean said.

Also, what about the Donald Davidson claim you briefly mention? That has no evidence at all behind it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am investigating the Davidson material. I took a long weekend in the mountains so haven’t been able to track down her citations yet. I will post something when I have something to report, so please check back.

I think MacLean said exactly that: that libertarians didn’t mind selling out Black citizens to advance their agenda. Chodorov’s “paean to the development of liberty” means little since his ideas of liberty were near-perfect alignment with the ideas of segregationists and racists: favoring the privatization of schooling, opposing civil rights acts, and opposing fair employment measures. I agree, that this version of “liberty” makes quite clear where his sympathies were.

LikeLike

“that libertarians didn’t mind selling out Black citizens to advance their agenda.”

Breed-specific legislation (BSL) is a serious problem. It treats all members of a dog species as having the exact same characteristics, characteristics which have not been bred into those dogs, but which some owners choose to train their dog to have.

You don’t mind selling out dogs like Rotweilers or Pit Bulls to advance your agenda of MacLean’s attack on Buchanan and thus libertarians/conservatives. Your entire essay says not one word about BSL, therefore I must, as a chronicler and reporter on your blog entries, conclude that you don’t care about BSL even enough to address their needs or concerns.

Didn’t somebody say recently that absence of evidence is not evidence of absence? Oh, nevermind, they must be wrong.

LikeLike

Cool! My blog has a “chronicler and reporter”! What’s the pay for that? Do you get health insurance? Is there dental? Or is it one of those internship deals where you only get college credit?

Hey, it was me! I was the one who talked about evidence/absence thing!! It was me, right?

Regarding the whole dog-breed thing, I’m afraid you are too clever for me to understand you. Sorry, us liberals can be slow on the uptake. Maybe explain it to me again? Using smaller words, maybe? Or perhaps typing slower so I can follow along? Remember, you sometimes need to teach to the slower kids in the class.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I completed my BA, MA, and PhD in History at the University of Houston in History in 2002, 2007, and 2012 respectively. My ex-wife did her BA at UH in PoliSci in 2003 before going onto Fordham for her MA 2005 and UT for her JD 2013. While undergrads in the 1990s we became acquainted with one of the UH political science professors, now dead, Ross Lence. He supervised my ex’s honors thesis in 2002-2003 which was more or less a civil libertarian’s critique of the Patriot Act. Lence was an incredibly kind man, cared deeply about testing ideas, and mentored a large number of students but he was also a die hard libertarian ideologue. In 1992 he edited John Calhoun’s writings for the Liberty Fund. In concert with Lence, the poli sci dept also employed other libertarian ideologues such as Don Lutz and Andy Little. I took an undergrad govt class Little. Later when in grad school, we once attended an Astros ballgame together as our kids were close in age and I spent a long time talking about Calhoun and tariffs with Little because I was working in antebellum political and social history in grad school; once in his home I saw he owned a 10-12 volume edition of Calhoun’s complete works but was also aware that he used the Lence edited Calhoun book from Liberty Fund in his courses as well. Again, Andy and I might have substantial disagreements about the role of government in society, but he was a great teacher, mentor and friend to many students who passed through the poli sci or later Honors College programs. Finally, Lence, Lutz, and Little all advanced libertarian ideas in courses at UH by emphasizing not just Calhoun, but also Rothbard, and the important Texas paleo-conservative link at the right leaning Catholic University of Dallas, Willmoore Kendall. Kendall, of course, was forced to leave Yale after helping Buckley found the National Review and landed on his feet in Texas at the Univ of Dallas….

The libertarian admiration for Calhoun is very, very, very longstanding. I offer only my tangential connection and acquaintance with these 1990s libertarian ideologue/scholars as an example of what I imagine is quite common across southern university landscapes more generally. The link between Calhoun, massive resistance, and 1990s libertarian think tanks is very, very real.

LikeLike

I’ve been a libertarian academic, active in IHS, Cato, etc, for almost 30 years, attendee of several liberty fund conferences, and I’ve never heard of Ross Lence, Don Luntz, or Andy Little.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So? Who cares who you know? Does anyone know you? There are lots of you guys and frankly none are top rated scholars outside your own circles.

You imply that because you don’t know them that they aren’t relevant, but that’s nonsense. These guys influenced many hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of students. They edited multiple publications for the Liberty Fund, directed and advised students at one of Texas’s only three public R1 universities, and routinely coordinated libertarian minded workshops in Texas, Montana, etc.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I would know if they were libertarians with any influence. Out of curiousity, I looked up Lutz, he runs a website called the Imaginative Conservative. I.e.., he not a libertarian by self-description. Liberty Fund has lots of scholars it works with who are conservatives, not libertarians. Paleo-conservatives are also not libertarians, and I can’t recall any libertarian ever expressing admiration for Kendall, he’s a non-entity in libertarin intellectual circles. You seem to commit a common fallacy, conflating Russell Kirk-stye decentralist conservatism with libertarianism.

LikeLike

Those of you who have the “not really a libertarian” square on your bingo card may now fill it in.

More seriously, I offered the example of Felix Morley in my original post as a libertarian who admired Calhoun. And Rothbard, and I think the current Mises Institute, are both libertarians and paleo-conservatives and they sure do like them some J.C. Calhoun over there: https://goo.gl/JQuJoP

LikeLike

I second what David Bernstein says, and I’m over 60, spent 30 years in the academy, and have been involved with libertarianism and its various supporting institutions since my college days. It is impossible that these persons can have had any important part in the libertarian movement without my having ever heard of them.

Some reading this will consider my saying so as a reason to insult or dismiss me, as has happened to David when he bothered to chime in. (Free and polite discussion, anyone?) But I hope at least some others will allow themselves to believe it, as a piece of evidence to be weighed like any other.

LikeLike

I regret that the original poster of this comment took a hostile and personal tone as well.

But let us not get distracted by trying to evaluate the reputations of the editors of Calhoun’s works. I think these are the important points.

SOME libertarians obviously admire Calhoun’s work. Many of those at the Mises Institute for example. And whoever is buying this book published by the liberty fund:

https://www.libertyfund.org/books?author_reversed=Calhoun%2C+John+C.

MacLean relies on the public choice theorists themselves to note the parallels between Calhoun & public choice. I’ve discussed the T&C article in my post and elsewhere on this comment thread. But here’s a quotation from her other source, Aranson:

“My principal thesis is that Calhoun’s political thought, when read in the light of modern public choice theory, forms a coherent whole, complete in its entirety,including within it even those parts that appear to be contradictory. Earlier interpretations of Calhoun’s thought remain devoid of an overarching theory that would allow for unification. But public choice theory makes possible such unifications of observations and truth claims, which once seemed impossible.”

Those who object to MacLean invoking Calhoun should first object to T&C and Aranson for leading her to that conclusion. Or ask why public choice theorists are engaging with Calhoun at all if not to use his theories to bolster their own?

LikeLike

Never heard of Calhoun in a libertarian context. Been a card-carrying Libertarian for twenty years. I’m sure you know better than me what Libertarians think, though. Go ahead, tell me what I think, I’m waiting with baited breath.

LikeLike

Y’all have cards? isn’t that against the whole “individualist” thing?

Unless you’ve been eating worms, it is “bated” breath. And, because my pedantry has no bounds, I’ll be happy to tell you what libertarians think! Thanks for asking! Look at some of my other posts! No need to thank me, us smug liberals live for this kind of thing!

You know, I posted a link to Felix Morley’s piece on Calhoun and several people have noted Rothbard’s admiration for Calhoun so there’s a couple libertarians right there. Or you can read the sources MacLean cites for Calhoun and public choice theorists. They are, I believe, both authored by public-choice theorists, but I’m not sure they carry cards. Maybe you could ask them at your next meeting? Anyway, here they are:

Aranson, Peter H. 1991. “Calhoun’s Constitutional Economics.” Constitutional Political Economy 2 (1): 31–52.

Tabarrok, Alexander, and Tyler Cowen. 1992. “The Public Choice Theory of John C. Calhoun.” Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics (JITE) / Zeitschrift Für Die Gesamte Staatswissenschaft 148 (4): 655–74.

Have fun!

LikeLike

In the pieces MacLean cites by economists (not public choice theorists) about Calhoun, they close by condemning Calhoun’s lack of morality. Somehow, she left that part out, as did you (I doubt you read the relevant source material).

LikeLike

Ah, previously you let us all fill in the “Not a true libertarian” square on our bingo cards. Now we are kicking out certain scholars who write on public choice theory as “not public choice theorists.” Man, your membership rules are strict!

1. Speaking of not reading the source material, if you go back and read the post, you’ll see I acknowledged that part explicitly.

2. Forgive me if I don’t see a condemnation of slavery by authors writing in the 1990s as an example of ethical bravery or leadership.

3. Neither article really explains how slavery can be so neatly excised from Calhoun’s theories of democracy. This is particularly a problem for Aranson since he argues that public choice theory brings a complete unity to Calhoun’s writings except (abracadabra!) for slavery. He offers no explanation for this but clearly realizes he has to omit slavery from his account so he does. How can public choice theory somehow account for all of Calhoun except for the most morally reprehensible part? It’s a mystery, but oh, so convenient for him. (see, I did read the source material, so nyah!)

4. Slavery or not, the point MacLean makes about Calhoun is that he developed his theory to limit democracy’s reach over the extreme wealth which slavery represented. Like Calhoun, public choice theory is designed to limit democratic accountability over the extremely wealthy. The only difference is Koch’s $$ is in oil rather than human beings.

LikeLike

“Some libertarians embrace Calhoun” =/= “Calhoun is the ‘intellectual lodestar’ of Buchanan & public choice.”

MacLean’s book pushes for the latter claim and does so on exceedingly flimsy evidence by historical standards. She also fabricates the Donaldson link out of what appears to be no evidence at all.

A stronger claim can indeed be made that Calhoun influenced Murray Rothbard, BUT (1) MacLean did not write a book about Murray Rothbard, who is much further outside of the academic mainstream than Buchanan, and (2) Rothbard and Buchanan were not particularly fond of each other. In fact, in 1960 Rothbard wrote a review aggressively attacking and then dismissing the very same book by Buchanan that MacLean insinuates – without any evidence – is a continuation of a Calhounite intellectual lineage.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’ve been a libertarian academic, active in IHS, Cato, etc, for almost 30 years, attendee of several liberty fund conferences, and I’ve never heard of Ross Lence, Don Luntz, or Andy Little.

LikeLike

Rothbard argued with everyone so that means little.

Although you put “intellectual lodestar” in quotation marks, I do not see MacLean using that term (if I am in error, can you supply the page number?). I do not see that MacLean argues that Buchanan, or anyone else, looks to Calhoun and tries to align their arguments with his (excepting possibly Rothbard). What I see is MacLean drawing an analogy between Calhoun’s 19th century goals and 20th-21st century libertarian goals.

In no way does MacLean argue that Calhoun was a “lodestar.” She argues that Buchanan and others in the 20th century “mirrors” (p. 1) that Calhoun. Koch-funded libertarians (not necessarily Buchanan) had an “appreciation” (p. 2) for Calhoun (citing Rothbard here. . She pointed out a parallel between Buchanan & Tullock’s “minority-veto power” of the constitution and Calhoun’s similar idea, and argues that Madison would have rejected B&T’s ideas as he did Calhoun’s (p. 81). She claims that the libertarian’s “cause…cause traces back to John C. Calhoun” (p. 224). And, in her conclusion she writes, “Now, as then, the leaders seek Calhoun-style liberty for the few–the liberty to concentrate vast wealth, so as to deny elementary fairness to the many.” (p. 234).

That is the entirety of her connections between Calhoun & 20th century libertarian thought. She is EXPLICITLY drawing the analogy herself. She is not making the argument you are claiming she is making. Again, if I have missed something in the book, where she makes the claim you say she did, I would be grateful if you pointed it out to me.

LikeLike

I can’t speak to who wrote that intro =) but in interviews about the book, MacLean has repeated the exact same characterization. Her discussion of Calhoun in later chapters should accordingly be interpreted as consistent with its claims…which doesn’t speak very well to her as being a careful historian on this point.

Re. Buchanan on the unlimited accumulation of property, I’m not 100% clear what you’re looking for. But it might surprise you to learn that Buchanan advocated a confiscatory estate tax on all estates over a certain amount on the grounds that it would improve social equity in a Rawlsian sense. MacLean makes no mention of that and does not appear to be aware of Buchanan’s position on something that I suspect she would likely agree with. It’s a major clue that she did not competently assess her subject matter and it also calls her assessment of other parts of Buchanan’s work into question.

LikeLike

“Intellectual lodestar” is on p. xxxii.

The full quote by MacLean reads:

“The first step toward understanding what this cause actually wants is to identify the deep lineage of its core ideas. And although its spokesperson would like you to believe they are disciples of James Madison, the leading architect of the U.S constitution, it is not true. Their intellectual lodestar is John C. Calhoun. He developed his radical critique of democracy a generation after the nation’s founding, as the brutal economy of chattel slavery became entrenched in the South – and his vision horrified Madison.”

I’d say from that passage that she’s about as explicit as one could possibly get in making that charge of a direct Calhounite lineage to Buchanan.

The reason I point to Rothbard is that MacLean specifically enlists his Calhoun-friendly writings in the 1960s to bolster her suggestions throughout the book that ‘Calculus of Consent’ is a derivative of the Calhounite intellectual tradition. This is a historically unsound argument given Rothbard’s deeply hostile take on the very same book.

LikeLike

Errghh….. That introduction…. .I swear it was written by someone else. Point taken on “lodestar.”

Nonetheless, I think MacLean is very careful about her argument throughout the book and her argument cannot be dismissed, as you seem to do, because of one clumsy word in the introduction. I would be much more likely to agree with you if, instead of pouncing on a single word, you could point me to Buchanan’s writings that argue AGAINST the unlimited accumulation of property or how property rights could be checked in some cases by majority rule.

LikeLike

It’s hard for me to follow reasoning that says that X held ideas A and B, and that Y (with no documentable connection to X) also held ideas B, and thus Y must necessary hold idea A, condemning everyone who holds B to have the attributes of someone who promotes A.

Possibly idea B is bad on its own, but there is no need to make a connection between X and Y — simply attack idea B. The trouble with doing so is that MacLean is not intellectually prepared to attack idea B, because she admits to knowing nothing about the school of academia which studies B.

LikeLike

“how property rights could be checked in some cases by majority rule.”

Oh, no. No, no, no. Property rights must be absolute. The less property you have, the smaller a minority you belong to, the more important it is for that property to be protected. Even the rich must be protected from the whims of the majority. If you look at laws like Jim Crow, and then look at the private property of railroads, you will see that the railroad would rather have conserved their property and allow it to be used by all races. What gains a railroad to have to have multiple sets of bathrooms, multiple waiting rooms, and multiple coaches?

LikeLike

Regarding this larger comment, you raise an interesting point when you note:

“What she cares about is his actions and his public statements. In those, she clearly shows, Buchanan worked hard to support every move the segregationists made in Virginia. Who cares if he did so because he was defending some strange view of “liberty” rather than white supremacy? The effect at the time and the place were the same. So, was Buchanan a racist? Who cares? What is important is that he worked hard in support of racist policies in Virginia in the 1950s, which is what MacLean shows.”

I’d answer quite simply that no. Actually she doesn’t show that at all. She claims repeatedly that Buchanan worked in support of segregationists, but if you check the footnotes she provides for that claim they end up being exceedingly thin. She actually has no statement from Buchanan himself to that effect. To make it stick she has to import other segregationist figures, and then use unsupported insinuations and speculative reasoning to connect them to Buchanan.

But far more problematic for MacLean is that she actually omits pertinent evidence that conflicts with her narrative of speculatively connecting Buchanan with segregationism. One notable example is William H. Hutt, an emeritus economist from the University of Capetown who Buchanan recruited to come to UVA as a visiting professor in 1965. Hutt’s main claim to fame at that point was as an academic opponent of South African Apartheid. He had just written a book – “The Economics of the Colour Bar” – applying a public choice framework to attack the Apartheid regime. He was also subjected to direct persecution by the South African government, which attempted to limit his academic freedom and at one point in the 1950s even seized his passport to prevent him from spreading anti-Apartheid views abroad.

Buchanan knew all this about Hutt when he recruited him for UVA. After Hutt arrived he gave several public lectures expanding on the themes of his recent book, condemning Apartheid. During his year at UVA he also expanded this line of argument specifically to the similarities between Apartheid in South Africa and the segregationism he was seeing in the American South. Hutt even wrote a short article in 1966 while at UVA spelling out the link between the two.

None of this material is particularly difficult to find. It also seems highly pertinent to your question above about what Buchanan did while living and working amidst a segregationist political system. You state that he did nothing to “rock the boat” of segregation. It certainly seems to me that bringing in a well-known Apartheid critic who then gave multiple lectures comparing Apartheid to what he saw in 1960s Virginia would constitute “rocking the boat.”

MacLean only makes one passing reference to Hutt’s arrival at UVA though (p. 59), and it says nothing about the subject he was actually working on while at UVA – his economic criticisms of Apartheid, as extended to segregation in the US (instead she characterizes Hutt by his far more obscure and decade-old book criticizing labor unions – which MacLean apparently believes can do no wrong). It would therefore seem to be the case that MacLean not only misrepresented her evidence linking Buchanan to segregation, but she also actively left out a pertinent piece of evidence showing that Buchanan actively recruited a staunch critic of segregation to his department.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Sorry for the accidental deletion and thank you for mentioning this blog on your own.

Regarding Hutt:

I don’t think that MacLean omitting Hutt’s 1965 activities is much of a criticism. She discusses Hutt’s anti-union work in the context of the anti-union work Buchanan was sponsoring in the 1950s so that seems appropriate.

As for the anti-apartheid work, it is important to remember that 1965 is a MUCH different time than the 1950s. Segregationists had been routed. They lost decisively through the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act (opposed by libertarians, btw, esp. Article II) and the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Most who had lined up against Civil Rights did an abrupt about face. For example, William F. Buckley Jr:

Even arch-segregationists, like George Wallace and J.J. Kilpatrick were backfilling as fast as they could. So the political climate was much different. So, an anti-apartheid book of 1964 and speaking about it in 1965 is all happening in a much different climate.

MacLean is NOT arguing that Buchanan was a racist, she is arguing that Buchanan saw the massive resistance movement as a way to advance his own political agenda and didn’t care if it helped Black citizens or not. Hence, in 1965, when massive resistance had collapsed, Buchanan was fine turning elsewhere to advance his policies. So it is perfectly consistent with MacLean’s case since it does not turn on proving that “Buchanan was a racist.”

LikeLike

My larger point on Hutt is that MacLean clearly saw evidence of Buchanan bringing him to UVA in 1965 in the papers she searched, but then opted to omit anything about what Hutt did while he was at UVA. His labor union book was over a decade old at that point.

Hutt’s lectures and writings from his time at UVA are almost entirely focused on his anti-Apartheid book, which had just been published. He also explicitly identified its parallels with segregation in Virginia in multiple lectures and a published article during his time there.

That seems like highly pertinent information to include if one’s aim is to ascertain the Thomas Jefferson Center’s relation to the segregationist politics of the day. It’s also highly unlikely that Buchanan would recruit a faculty such as Hutt to give anti-segregationist lectures if his objective was to provide a deep intellectual foundation behind the Byrd machine and Kilpatrick’s journalism, as MacLean alleges. Also – the Byrd machine was still very much in control of Virginia politics in 1965. Its first cracks didn’t appear for another year when Spong ousted Robertson in the senatorial primary (and that was widely perceived as a dramatic upset). The real demise of the Byrd machine didn’t happen until 1969 after Harry Sr. was dead and Harry Jr. couldn’t hold the Democratic Party together against Linwood Holton. By that point, Buchanan had moved to UCLA.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, the Byrd machine was in power. But massive resistance, and dreams of privatizing schooling, even in Prince Edward County, were dead. Hence, time to move on.

LikeLike

Two more quick points after checking MacLean:

1. She very clearly portrays the mid-1960s Jefferson Center (p. 90-93) as being in service of the Byrd machine and claims the Goldwater movement as the supposed link.

2. In the passage on p. 59 where she discusses Hutt, she strongly implies that Buchanan brought him over because his criticisms of labor unions could be used to show “the South’s state officials were right about the labor movement” and thereby satisfy Byrd. Her footnote provides no basis for this claim.

LikeLike

1. I don’t follow you. She recounts how Buchanan had ALWAYS been tied to the Byrd machine, GW made no difference to that one way or the other. And, to repeat myself, being tied to the Byrd machine was NOT the same thing as being tied to massive resistance, which had collapsed by then. Indeed, in those pages and the following she shows quite clearly that the appeals of massive resistance, which were so potent in the 1950s, were dead, dead, dead. So, Hutt’s appearance is in line with those changes. And, to repeat myself again, you cannot enroll something that happened in in 1965 to somehow “falsify” actions of 5-10 years before.

2. If you are referrring to the Medema article, I don’t have it so can’t comment. But, I don’t think it even requires a citation to point out that Buchanan brought in anti-union economists because Virginia politicians were anti-union. Is that an outrageous claim to make? Or, is it just a big coincidence? Not sure what your point is here.

LikeLike

Griffin v. Prince Edward wasn’t even decided until 1964, and after they reopened the public school by court order it remained almost exclusively black for another decade. The private Prince Edward Academy persisted until the 1970s when it lost its tax exemption for refusing to integrate.

LikeLike

There’s the problem though – her footnotes, her archival evidence etc. actually DON’T support the contention that Buchanan was “tied to the Byrd machine.” She’s making a bizarre argument-by-geography that has little more to commend it than the fact that Buchanan taught at the University of Virginia in the 50s and 60s. She goes from there to argue that Buchanan necessarily dealt with academic administrators who dealt with other administrators who – eventually – dealt with politicians, who were connected to the Byrd machine. But that’s not “evidence” – it’s an innuendo-laden game of six-degree-of-separation that could just as easily be used to make a similarly specious claim about every single faculty member, student, or even janitor at the University of Virginia in the same time period.

The same problem afflicts her entire portrayal of Buchanan’s relationship to Brown v. Board. MacLean essentially has him showing up at UVA and building up a vast repertoire of theories about constitutional political economy for the purpose of intellectually justifying the Byrd operation and its other segregationist kin. It’s a fancy tale, but it has no evidence behind it. She doesn’t even understand the basic history of Buchanan’s academic career. He was actually in Italy on a 2 year Fulbright when Brown v. Board happened, spending his time over there studying comparative constitutional systems at a string of Italian universities and legal institutes. He was about as detached from the decision as an American academic possibly could be, and when he got back to the US there’s no evidence his subsequent scholarship had anything to do with engaging Brown, either directly or indirectly, or assisting the Byrd org in doing the same. MacLean literally made all that stuff up and strung it together by little more than common dates and a common geography. That’s not history – it’s an Alex Jones-style conspiracy theory, with about the same amount of intellectual credibility.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really do think you are misreading the book. MacLean does not claim that Buchanan had “segregationist motives” or that he developed his theories in service to segregation. She claims that Buchanan acted with indifference to African-American citizens. He wanted privatized schooling for his vision of “liberty.” Segregationists wanted privatized schooling for racial purity. This is an example of what Derrick Bell called “interest convergence.” If there is evidence that Buchanan was concerned about African American welfare, by all means let’s see it. If not it is pretty clear that Buchanan was happy to work with segregationists to achieve what segregationists most wanted: private schools. That he might have wanted them for “liberty” does not change that fact and does not absolve him. She is not addressing his MOTIVES at all. His motives are irrelevant. What is relevant is that the policies he wanted would serve segregation, and he was fine with that. That is her argument. Unless there is a treasure trove of material somewhere that shows that Buchanan (or, to be frank, any other libertarian of the time) had a plan to deal with racial inequality we are left with: 1. Substantial evidence that libertarians, including Buchanan, supported, and provided “race-neutral” intellectual arguments that segregationists wanted, and 2. No evidence that they were the least bit concerned with African-American voices protesting those policies. Indeed, MacLean documents Buchanan’s complete silence on Prince Edward County and his belief that “Virginia, as a state, has, in my opinion, largely resolved her own problems” in education. (p. 73).

The plain and simple fact is, you cannot win this argument by simply attacking and trying to explain this situation away. It is time for you to build a positive case that Buchanan at the U of Virginia had any concern whatsoever for racial justice. Otherwise, Buchanan’s silence damns him.

LikeLike

I gave you a case that Buchanan cared about racial justice while at UVA. He recruited and hired a visiting professor whose main work was on anti-Apartheid economics, and whose time at UVA was spent applying those arguments to segregation.

You waved your hands and declared it didn’t count because it was in 1965, even though (1) the Byrd machine was still very much in charge of the state then, (2) segregationists in Virginia were still waging a battle against school integration via private academies despite all their court setbacks, and (3) MacLean explicitly asserts at multiple points that Buchanan was still catering to the Byrds and the segregationists in the mid 60s.

Like MacLean, it would appear that you are struggling with evidence that complicates a thesis you already accepted as “true” despite its own thin attestation.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My point is simply this: Buchanan sponsoring an anti-apartheid economist in 1965 does not mean that his proposals for privatized education did not serve segregationist interests in 1959. Nor can you possibly believe that.

You seem to think MacLean’s argument (and my argument) depends on Buchanan being a racist. It does not. See my reply to wilsonle262 below.

LikeLike

“The plain and simple fact is, you cannot win this argument by simply attacking and trying to explain this situation away. It is time for you to build a positive case that Buchanan at the U of Virginia had any concern whatsoever for racial justice. Otherwise, Buchanan’s silence damns him.”

Not really. It only damns him if you begin with the axiom that Buchanan is a crypto-racist. An assertion of that nature needs to be proven, not assumed. The title of your post is “Was James Buchanan a racist?” Like it or not, answer in the affirmative requires positive evidence that he was, in fact, a racist. Was everyone who was not as fervent a supporter of a variety of civil rights initiatives as you would have liked also, categorically, a racist? If so, then the term becomes so expansive that we may as well not invoke and your allegation relies on a not much more than a hunch.

After the welter of facts and evidence Phil has patiently offered up here–some of which would even indicate that Buchanan was sympathetic to progressive racial policies– you owe him a better response than to simply trot out this argument from silence and declare victory. This is weighty intellectual history we’re dealing with here, and I’ve been thoroughly enjoying the back-and-forth here, but this is weak sauce.

“Buchanan wasn’t enough of an anti-racist by my 21st century standards, therefore he may as well have been a racist” isn’t gonna cut it for serious historians. Well, it shouldn’t, at least. Geez.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Weak sauce for the goose is weak sauce for the gander. (no, I’m not sure what that means either, but I had to say something, right?)

OK, I said this explicitly more times than I care to count on this post/thread, but let me shout it loudly so maybe it sticks: MACLEAN AND I ARE NOT CALLING BUCHANAN A RACIST! Indeed, I explicitly write in my post that whether he was a “racist” or not is completely irrelevant to my evaluation of him. MacLean is also quite explicit about this point and warns readers not to make the mistake of thinking that racism is the only key to her explanation for massive resistance:

“It is true that many observers at the time, and scholars since, have reduced the conflict to one of racial attitudes alone, disposing too easily of the political-economic fears and philosophical commitments that stiffened many whites’ will to fight. So a ‘both/and construction would be reasonable.”

What she HAS argued, and I agree with, is that Buchanan was indifferent to Black citizens’ concerns. What y’all are asking us to believe is that a white man, born in 1919 and spent his entire life in the south (save for a brief time in WWII), who was embedded in a segregated university funded by a segregated political machine, who wrote to correspondents that there was no racial problem in Virginia, who advocated the same policy positions as segregationists, and who in TWENTY VOLUMES of published writings never wrote anything on racial justice, was really concerned with the lives of Black citizens and a racial egalitarian.

Buchanan was simply a victim of “white ignorance” in Charles Mills’s phrase. He was not a “crypto-racist” nor does my argument depend on him being one. Finally, merely produce some written evidence from Buchanan that shows he was different from my characterization of him.

LikeLike

Sorry, the MacLean quotation is on p. 69.

LikeLike

“What is relevant is that the policies he wanted would serve segregation,”

No. The policies he wanted were *thought* by segregationists to be helpful to their aims. You cannot say that X wants policy A and Y wants policy A because B, and therefore X is fine with B, because Y could easily be wrong about policy A bringing about state B.

For example, eugenicists said that a minimum wage could be used to hurt the employment of black people. Obviously wrong, natch. But does it condemn the modern-day minimum wage advocate to a hell of damnation as a racist? Of course it does not.

LikeLike

I’ve never heard this about eugenicists and the minimum wage. It doesn’t make sense to me, since American eugenicists were concerned about things like sterilization, immigration restriction, and things like that. Do you have source for that claim?

LikeLike

“What y’all are asking us to believe is that a white man, born in 1919 and spent his entire life in the south (save for a brief time in WWII)”

A minor issue of detail with your portrayal, but I call attention to it specifically because it illustrates the carelessness with which you approach Buchanan even as you make several extremely strong assumptions about the role of race in his upbringing. Prior to arriving at UVA, Buchanan spent 4 years getting his doctorate at Chicago and 2 years doing a Fulbright in Italy. The last I checked, neither Chicago nor Italy are in the American South.

Concerning your longer comment, I’ll simply ask this. You keep asserting that Buchanan obtained his position at UVA through some sort of relationship with segregationist politicians (in the latest post you say he was “embedded” there by the segregationists), strongly implying that his work was intended to bolster them (and yes – you’ve made this insinuation and asserted it to be true whether he was personally racist or not). If that’s the case, then surely you can point me to specific correspondence or other similar archival records that demonstrate Buchanan’s connections with Byrd or other segregationists, as distinct from the normal practices of applying for and getting an academic job. If your claim is true, you need to be able to minimally document it in evidence. So far, neither you nor MacLean have done so.

LikeLike

You are quite right about his time in Chicago and Italy. I am writing quickly and simply forgot that. I will point out that MacLean argues that his time away from the south only served to amplify his sense that these elitists didn’t understand him and increased his resentment toward the big shots up north.

You keep strawmanning your opponents’ arguments. I never said he was “embedded by the segregationists.” I said he was embedded in a segregationist university–deliberately using the passive voice (I hope my PhD advisor didn’t see me do that!). You keep demanding evidence of the state of mind of Buchanan or those he worked with. “Prove he was a racist–that he believed blacks were inferior!” “Prove he wanted/desired/hoped for continued segregation.” Given the strength of those claims, naturally the evidence MacLean or I present falls short. I’ve repeated this so often that I feel you are deliberately ignoring it: WE ARE NOT CLAIMING THAT BUCHANAN WAS A RACIST OR SEGREGATIONIST!!!!!! We are claiming that Buchanan and the segregationists had a convergence of interests: Segregationists to preserve segregation; Buchanan to shrink governmental power. Their interests met in the privatization of schools in Virginia; they each were using the other to advance their ends through the same means. If you have an argument to advance toward THAT claim please do so, but quit trying to make me defend a claim I am not making. You’ll note that this claim is perfectly consistent with the events of 1965, since it in no way turns on Buchanan bearing deep-seated racial animosity towards anyone. To that extent, bringing in an anti-apartheid speaker to help bust the unions (for freedom!) is fine. After all, since libertarians opposed fair employment practices, business-owners could always refuse to hire African Americans anyway (I don’t know about Buchanan’s view of things like the FEPC, I’d be happy to learn though, perhaps I’m wronging him).

And, again, I will ask for evidence, from Buchanan, from the 1950s that he was a racial egalitarian. It is all easy to try to pick apart someone else’s case, but far harder to build one that he gave a damn about racial justice in the face of his overwhelming silence before the Civil Rights Act. For example, what was his position on Article II of the CRA on public accommodations? Did he criticize it, as every other libertarian did, as an unjustified infringement of property rights?

Finally, I’m working on a new post on the Davidson stuff. If you wanted to keep your powder dry and wait until that is up, today or tomorrow and then that might make this conversation less repetitive.

LikeLike

John – Again, I’m not asking that you “prove Buchanan was a racist” despite your protests otherwise.

It’s fair to note that there does seem to be a degree of pivot occurring in the MacLean camp between posting innuendo that suggests Buchanan was a racist (e.g. her claim that he didn’t like the number of black people at UCLA, plus all the lengthy digressions she does on Calhoun, Davidson, Byrd, and others) and then retreating to a plea of innocence whenever pressed to validate these depictions with sources. That’s problematic in itself for MacLean’s work (and your defense of it), even if you insist you aren’t trying to show Buchanan is a racist. Otherwise, why include several strong innuendo to that effect?

But more to the point, what I’m asking you to prove is simply this:

I’d like to see your evidence that Buchanan had *any* connection to Byrd at all, or that he influenced Byrd or the segregationists’ strategy, or that they were even aware of him and his work.

Even if we hold that her innuendo about racism is just a side story, MacLean certtainly paints Buchanan as a major intellectual figure hovering somewhere in the background of the segregationists’ school strategy, and you appear to agree with her. If that’s the case it should be easy for you to show – with documents – that segregationists were taking his work, citing it, praising it, deploying it in their own activities etc. on a regular basis. As it stands right now, MacLean’s footnotes do not rise to that minimal evidentiary expectation.

LikeLike

Libertarians such as Chodorov, Friedman, and Buchanan believed, that private schooling with vouchers and would be better for all concerned. That may have been naive or even wildly ignorant and insensitive. It’s hard to look at the history of court-ordered segregation, including busing in the North, and the shambles it left many public school systems in, including most major urban systems, and the resulting de factor segregation, and be smug about how they were wrong and the liberals were right.

LikeLiked by 2 people

But “smug” is my default setting!!

1. I know that the libertarians of the time said that private schooling would be “better for all concerned.” They said it in the face of African American Virginians screaming that privatization was simply a way to perpetuate segregated schooling (why didn’t the libertarians listen or even acknowledge their voices?

2. Virginia had demonstrated quite clearly that it could not afford to fund two separate school systems, what evidence did the libertarians have that it could afford three? (White, Black Integrated).

3. Did the libertarians of the time predict the problems you said arose later? If so, how did they argue that vouchers would fix those problems? What evidence did they have for those claims?

4 Historians HATE counterfactuals such as these: “Maybe if the vouchers would have been tried, these problems would not have happened!” It is hard enough to figure out what DID happen without worrying about what COULD HAVE happened. In this case, however, we have an empirical test of the libertarians’ program when Prince Edward County in Virginia privatized their school system. Was it “better for all concerned?” Well, as MacLean reports, “Local black youth remained schoolless from 1959-1964, when a federal court intervened to stop the abuse.” Again, these were the voices Buchanan et.al. ignored. And, again, in ANYTHING Buchanan wrote at the time is there ANY evidence that he acknowledged the utter failure of private schooling to help “liberty?” I suspect it is much more likely he would have decried the federal court order as “overreach” by a tyrannical federal government.

LikeLike

If we agree that libertarian economists who supported vouchers believed that this would benefit both blacks and whites, and are only discussing whether they were insensitive to social and historical context, then the whole issue is absurd. Economists being accused of ignoring social and historical context when pushing their ideas? This is something economists get accused of constantly. But please note that in 1959, when Buchanan was supporting full privatization of schools, Brown had been around for five years, and virtually no schools in the south had been desegregated. I believe that as late as 1962, the figure was something like 2%. So this wasn’t a case of him trying to undermine successful school desegregtion, but noting that schools were not being desegregated, suggesting an alternative to both Jim Crow and unsuccessful court orders. And as noted, one can hardly claim that court-ordered desegregtion was ultimately a great success.

LikeLike

Are you simply going to ignore Prince Edward County? Where your solution was tried and the resulting disaster for African Americans? Can you square the court order that ended that experiment with your libertarian principles? Is your position that education for African Americans was BETTER when they had no schools?

LikeLike

As I’m sure you’re aware, in PE County African Americans boycotted the vouchers for the few years the vouchers existed, so of course the program was a “disaster” for them. Of course, court-ordered desegregation, and in particular busing, was a disaster in cities all across the United States. It didn’t just destroy the public school systems of many cities, but also encouraged suburbinization, pulling resources more generally out of cities. Should I judge the NAACP racist because the policies it supported from genuine good intentions worked out so poorly?

LikeLiked by 1 person

As I’m sure you’re aware, in PE County African Americans boycotted the vouchers for the few years the vouchers existed, so of course the program was a “disaster” for them. Of course, court-ordered desegregation, and in particular busing, was a disaster in cities all across the United States. It didn’t just destroy the public school systems of many cities, but also encouraged suburbinization, pulling resources more generally out of cities. Should I judge the NAACP as harshly as Maclean judges Buchanan because the policies it supported from genuine good intentions worked out so poorly?

LikeLike

So, VA created a market for vouchers, the customers didn’t want them, and that is somehow NOT the fault of those selling the product?

I don’t want to enter into a discussion of busing or suburbinization, that is getting too far afield from the present discussion.

LikeLike

Hi, looks like comments here are disappearing? https://twitter.com/PhilWMagness/status/886314020554383360

LikeLiked by 2 people

My fault! For the past 4 days I’ve been vacationing in Shenandoah National Park trying to manage the blog from my phone with spotty cell phone coverage. I managed to “approve” some comments twice in the process which, of course, sent them back to moderation. I am sorry about that and everything should be back to normal.

LikeLike

John Jackson writes (in a reply to Phil Magness): “Unless there is a treasure trove of material somewhere that shows that Buchanan (or, to be frank, any other libertarian of the time) had a plan to deal with racial inequality we are left with: 1. Substantial evidence that libertarians, including Buchanan, supported, and provided “race-neutral” intellectual arguments that segregationists wanted, and 2. No evidence that they were the least bit concerned with African-American voices protesting those policies.”

I’m not sure what you consider a “treasure trove,” but libertarians such as Rothbard were keenly interested in the civil rights movement and had a quite a lot to say about it. Rothbard contributed a 5,000+ word article to New Individualist Review in 1961 on “The Negro Revolution,” describing the civil rights movement, with all its diversity, in great detail (http://oll.libertyfund.org/pages/rothbard-on-the-black-revolution). The article is mostly descriptive and analytical but Rothbard concludes by describing the libertarian position as “oppos[ing] compulsory segregation and police brutality, but also oppos[ing] compulsory integration and such absurdities as ethnic quota systems in jobs.” (BTW on the question of racism and unions, referred to above in the context of W. H. Hutt, Rothbard adds: “some Negroes are beginning to see that the heavy incidence of unemployment among Negro workers is partially caused by union restrictionism keeping Negroes (as well as numerous whites) out of many fields of employment. If the Negro Revolution shall have as one of its consequences the destruction of the restrictive union movement in this country, this, at least, will be a welcome boon.”)

Rothbard was also sympathetic to the Black Panthers, writing in 1969 (http://rothbard.altervista.org/articles/libertarian-forum/lf-1-4.pdf) that the Panthers “have three great virtues: (1) their enormous ability to upset and aggravate the white police, simply by going around armed and in uniform — the supposed Constitutional privilege of every free American but apparently to be denied to radical militant blacks; (2) their considerable capacity for organizing black youth; and (3) excellent black nationalist ideas–particularly in emphasizing a black nation with their own land in such areas as the Black Belt of the South — as expressed in some writings of Eldridge Cleaver.” (Rothbard went on to criticize the Panthers, however, for their Marxism and violence.)

I offer these examples not to claim that Rothbard or the libertarians in his circle held what Mr. Jackson would consider the proper views, but to show that libertarians certainly did care about (state-sponsored) racism and were hardly blind or indifferent to the racial struggles of the 1960s.

BTW I suspect MacLean is unaware of Rothbard’s position on American slavery, as expressed in his Ethics of Liberty (1982) (https://mises.org/library/ethics-liberty): “We have indicated above that there was only one possible moral solution for the slave question: immediate and unconditional abolition, with no compensation to the slavemasters. Indeed, any compensation should have been the other way — to repay the oppressed slaves for their lifetime of slavery.” (He specifically suggests that plantations should have been turned over to the slaves — a position similar to his later view on post-Soviet transition, namely that state-owned enterprises should be privatized by giving equity shares to the employees.)

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for this comment. I agree that MacLean probably paid little attention to Rothbard. He is, however, one of the key figures in the book I’m writing. Rather than respond to you here, I am working on a post on Rothbard’s position regarding Black Nationalism in the 1960s. I hope it appears later this week. I hope you check back to see my response.

LikeLike

MacLean mayhave only paid a little bit of attention to Rothbard, but she paid enough attention to cite him, and misrepresent what he wrote. See: http://econlog.econlib.org/archives/2017/06/nancy_macleans.html#370726

(Had she paid more attention to Rothbard, however, she would have found plenty of things he wrote later in his career that are indeed blameworthy.)

LikeLike

Rothbard prided himself on his consistency througout his career. Those blameworthy things later in his career are perfectly consistent with the “Negro Revolution” article. Later this week….

LikeLike

I have now posted my thoughts on Rothbard and Black Nationalism if you are interested.

LikeLike

Regarding Calhoun, Phil has already noted that you understate the debt MacLean says Buchanan owed to him. Regarding libertarianism more generally, she makes the truly absurd claim on pages 224-25 that libertarianism traces its “lineage” to John Calhoun. This is far different than claiming that some libertarian ideas resemble Calhoun’s ideas. All you’ve got to support that is one article by Rothbard and the fact that Felix Morley reviewed a volume of Calhoun’s writings?

LikeLike

No, I’ll just rely on the same sources that MacLean does: the public choice theorists themselves who draw the parallels. Why don’t you refute them instead of me?

LikeLike

There’s an interesting pattern in these exchanges. MacLean’s work is to be read charitably, even when this requires excusing or ignoring specific things that she wrote (e.g. “lodestar,” etc.). Buchanan, et al., however, are not to be read in the same way. Instead, we can assume and infer all sorts of things merely because no one has pointed to evidence of the contrary. This is not the way honest intellectual inquiry should occur.

There’s no doubt that many libertarian and conservative intellectuals in the 1950s and 1960s had retrograde racial views (much as may liberal and progressive intellectuals of that period were blind to the evils of Communism). Many such figures are worthy of condemnation. Yet MacLean’s thesis extends well beyond such a modest (and, indeed, uncontroversial claim), and that’s where she seems to get herself in trouble. The things she says which are well-documented are unoriginal. The things she says that seem to be original, on the other hand, do not appear to be particularly well-documented.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There are also parallels between public choice and Marxist theories of the state. I myself have been struck by the similarity of many Marxist and libertarian critiques of the first New Deal. By the logic used above, we can say that the “lodestar” of libertarianism, and the greatest influence on James Buchanan, was Karl Marx.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Daniel Rodgers has noted the use of libertarians and other right-wing figures using (coopting?) Marxist language and concepts. You might find his treatment interesting:

Rodgers, Daniel T. 2011. Age of Fracture. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

As for “lodestar”… Can you support your argument beyond that one word from the introduction? Can you actually deal with the argument as she presents it in the book? Can you deal with the fact that she is basically making the same argument as public choice theorists have made about the harmony between public choice theory and Calhoun’s thought? Or are you just going to repeat “Lodestar! She said ‘lodestar!” No take backs!!!!!”

“My principal thesis is that Calhoun’s political thought, when read in the light of modern public choice theory, forms a coherent whole, complete in its entirety, including within it even those parts that appear to be contradictory. Earlier interpretations of Calhoun’s thought remain devoid of an overarching theory that would allow for unification. But public choice theory makes possible such unification of observations and truth claims, which once seemed impossible.” (p. 32)

Aranson, Peter H. 1991. “Calhoun’s Constitutional Economics.” Constitutional Political Economy 2 (1): 31–52.

LikeLike

“Was James M. Buchanan a racist? … In some sense, the answer is a trivial one: Buchanan was born in 1919 in Tennessee, where he spent his formative years, and as an adult he lived in Virginia, ground-zero for ‘respectable racism’ in the decade after Brown where his political allies and many of his colleagues were segregationists. Given those facts, it would be a remarkable thing if Buchanan did not think, at some level, that black people were not as good as white people in his heart of hearts.” – My grandfather fought against the Klan in the 1920s, then later my father fought against Jim Crow in the 50s & 60s. If they were living, I’d let them know this author says they “have to be” racists because of where they were born. As men who suffered during the MacCarthyite witchhunt, they’d find this author’s accusations of guilt by association very familiar.

LikeLike

You are not reading carefully. I never said that a white person of Buchanan’s description *must* be a racist. I said it would be remarkable if he was not. Your father and grandfather were such remarkable people and should be celebrated. I recommend David Chappell’s book: Inside Agitators: White Southerners in the Civil Rights Movement for a historical account of the brave people, like your father and grandfather, who fought the segregationist system.

My argument is this: Given the time and place we find Buchanan, it is not unreasonable to start with the presumption that he did not fight against segregation, since, as your own family experiences testify (backed up by Chappell) few white southerners did. But, note I said that is where we START. We then turn to what we can discover about them. In the case of your father and grandfather we find that they fought and, as you say, suffered. In the case of Buchanan we find someone who: 1. never spoke out against segregation. 2. advocated the policy positions favored by segregationists, and 3. wrote that perhaps African Americans were not responsible enough for self-governance (p. 35). Regardless of whether or not he was inspired by by Calhoun or Davidson, no one is disputing that he in fact did 1-3.

Please do not take my presumption, which is the opening of my argument, to be its conclusion.

LikeLike

Pingback: More Libertarians: Murray Rothbard and Competitive Racism | Fardels Bear

Critics have seized on this argument, perhaps because MacLean makes it on the first page of the book, thus sparing the critic from reading further before declaring her a bad historian….

Thus these critics can read the first page of the book, do a search for “Calhoun” online and show that MacLean is a dishonest researcher in the space of five minutes! Easy peasy!….

MacLean cites public choice scholars themselves who explain their debts to Calhoun. These articles have titles like “The Public Choice Theory of John C. Calhoun” and “Calhoun’s Constitutional Economics.” This is hardly “fabricating a claim out of thin air.”

The abstract of “Public Choice Theory of John C. Calhoun” reads….

To be sure, the public-choice authors note some differences as well as similarities between Calhoun and Buchanan’s thought, but it seems Calhoun’s influence on public choice theory originates with the public choice theorists themselves.

Here’s Don Boudreaux on MacLean and “The Public Choice Theory of John C. Calhoun”:

…the point of the Tabarrok-Cowen paper is not to show that Calhoun inspired Buchanan specifically or public-choice scholarship generally. Instead, it is a sober exploration of the extent to which Calhoun’s writings on constitutional rules and political decision-making did or did not anticipate public-choice scholarship on these matters. In the end, while Tabarrok and Cowen identify some overlap between Calhoun’s writings and those of modern public-choice scholars, they conclude that “[u]nlike Buchanan, Calhoun does not subscribe to normative individualism and contractarianism.” Because normative individualism and contractarianism were vigorously and openly embraced by Buchanan and play dominant roles in his life’s work, this fact about Calhoun is definitive proof that Buchanan was no Calhounite.

LikeLike

Bourdreaux is offering you a red herring. The sentences RIGHT AFTER she quotes T&C she explains the similarities she is pointing to. And, I will note, in all the accusations about MacLean misusing Calhoun by pointing out places the two thinkers differed, NONE of them respond to the clear parallels that concern Maclean. For the record from PAGE ONE of MacLean:

“Both Buchanan and Calhoun, coauthors, observe, were concerned with the ‘failure of democracy to preserve liberty.”

Since MacLean’s entire book is about how Buchanan wanted to restrict democratic control over property rights, you’d think Bourdreaux would have addressed this, instead of “normative individualism and contractarianism” which seem to have little, if anything, to do with this.

But wait! Can we trust MacLean to quote T&C correctly? Well the quoted phrase is the title of an entire subsection of their paper. The first paragraph of that subsection reads:

‘Democracy, for both Calhoun and Buchanan, is one of the most important means of curbing government’s tendency to oppression, but democracy is in noway sufficient. Calhoun writes that suffrage is the primary principle but “it would be a great and dangerous mistake to suppose, as many do, that it itself, sufficient to form constitutional government (13).” Buchanan concurs writing that the “monumental folly of the past two centuries has been the presumption that, so long as the state operates in accordance with democratic procedures . . . the individual does, indeed, have insurance against explotation… (Buchanan [1989, 55]).”‘ (T&C, p. 660).

MacLean’s citation of T&C is entirely appropriate as they clearly support the main argument she is making about Calhoun. Those, like Bourdreaux, who think otherwise should address her argument rather than these irrelevancies.

Oh, and she also cites Aranson, who makes similar claims, which her critics are completely ignoring.

LikeLike

Pingback: Libertarian Titles: A Top Ten List | Fardels Bear

Pingback: Faith, Hope and Charity in Academic Arguments | The Only Winning Move

Pingback: Reflections on Libertarianism and Racism | Fardels Bear

Pingback: School Vouchers, James Buchanan, and Segregation | Fardels Bear

Pingback: Arguing With Libertarians | Fardels Bear

Pingback: Charlottesville and Racism | Fardels Bear

Pingback: Should-Read: Fardels Bear: Was James Buchanan a Racist? Libertarians and Historical Research - Daily Economic Buzz

In 1956 Donald Davidson was still regarded as an important American poet, and the Southern Agrarians were a major factor in English departments. I believe that I had an Agrarian teacher as late as 1978. If Buchanan admired Davidson (who was indeed a hard core racist) it wasn’t unusual. In “Better than Plowing” Buchanan mentioned his sympathy for the Agrarians very explicitly, and the term “Leviathan” he used for big government was also Davidson’s term. (Hobbes used the term entirely differently).

LikeLike

I am not a libertarian but an academic economist familiar with Buchanan’s work. I also live in a highly segregated state: no, it’s not in a former confederate state, but rather the state of New York. Typically, whites and Asians attend well-performing schools while blacks and Hispanics attend poorly-performing schools. As well, the student bodies are quite homogeneous: in many districts a single group tends to make 90% or more of a student body. This is the result of policies pursued by the Federal Housing Administration, the public school system, and zoning laws as documented not by a libertarian, but by liberal scholar Richard Rothstein in a recent book. So by MacLean’s and your standards, and since these policies are usually supported by people who identify as liberals, it seems to me that if someone has thrown Blacks under the bus to adjust their political agenda it would be American liberals (as opposed to classical liberals). You should really spend some time thinking about that!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is not a “liberals v. conservatives” issue or a “liberals v. libertarians” issue. It is a racist v. non-racist issue. Rothstein’s solution is, of course, not less government as the libertarians would have it. It is rather government policies that are truly concerned with racial justice.

Property rights and private contracts among individuals were also incredibly powerful instruments for enforcing racist political agendas. See my post here:

LikeLike